Advanced Docker¶

Now that we are relatively comfortable with Docker, lets look at some advanced Docker topics, such as:

- Registry

- Porting a Docker image to a Registry & Repository (public and private)

- Managing data within containers

- Deploying containers on cloud services

1. Docker Registries¶

To demonstrate the portability of what we just created, let’s upload our built Docker image to a Docker Registry and then run it somewhere else (i.e. CyVerse Atmosphere).

In this exercise, you’ll learn how to push built containers to registries, pull those containers from registries, and run those containers on remote hosts (virtual machines).

This will benefit you when you want to deploy new containers to production environments where testing is not possible.

Important

So what EXACTLY is a Registry?

A registry is a collection of Repositories, and a Repository is a collection of Images. A Docker Registry is sort of like a GitHub Repository, except the code is already compiled, in this case, into a container. You must have an account on a registry. You can create many repositories. The Docker CLI uses Docker’s public registry by default. You can even set up your own private registry using Docker Trusted Registry

There are several things you can do with Docker registries:

- Push images

- Find images

- Pull images

- Share images

1.1 Popular Registries¶

Some examples of public/private registries to consider for your research needs:

- Docker Cloud

- Docker Hub

- Docker Trusted Registry

- Amazon Elastic Container Registry

- Google Container Registry

- Azure Container Registry

- NVIDIA GPU Cloud

- Private Docker Registry - not official Docker

- Gitlab Container Registry

- CoreOS Quay

- TreeScale

- Canister

1.1.1 Log into a Registry with your Docker ID¶

Now that you’ve created and tested your image, you can push it to Docker cloud or Docker hub.

Note

If you don’t have an account, sign up for one at Docker Cloud or Docker Hub. Make note of your username. There are several advantages of registering to DockerHub which we will see later on in the session

First, you have to login to your Docker Hub account.

If you want to authenticate to a different Registry, type the name of the registry after login:

$ docker login <registry-name>

Authenticating with existing credentials...

WARNING! Your password will be stored unencrypted in /home/tswetnam/.docker/config.json.

Configure a credential helper to remove this warning. See

https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/commandline/login/#credentials-store

Login Succeeded

If it is your first time logging in you will be queried for your username and password.

Login with your Docker ID to push and pull images from Docker Hub or private registry.

If you don’t have a Docker ID, head over to https://hub.docker.com to create one.

1.1.2 Tagging images¶

The notation for associating a local image with a repository on a registry is username/repository:tag. The tag is optional, but recommended, since it is the mechanism that registries use to give Docker images a version. Give the repository and tag meaningful names for the context, such as get-started:part2. This will put the image in the get-started repository and tag it as part2.

Note

By default the docker image gets a latest tag if you don’t provide one. Thought convenient, it is not recommended for reproducibility purposes.

Now, put it all together to tag the image. Run docker tag image with your username, repository, and tag names so that the image will upload to your desired destination. For our docker image since we already have our Dockerhub username we will just add tag which in this case is 1.0

$ docker tag username/appname:latest username/appname:1.0

1.1.3 Publish the image¶

Upload your tagged image to the Dockerhub repository

$ docker push username/appname:1.0

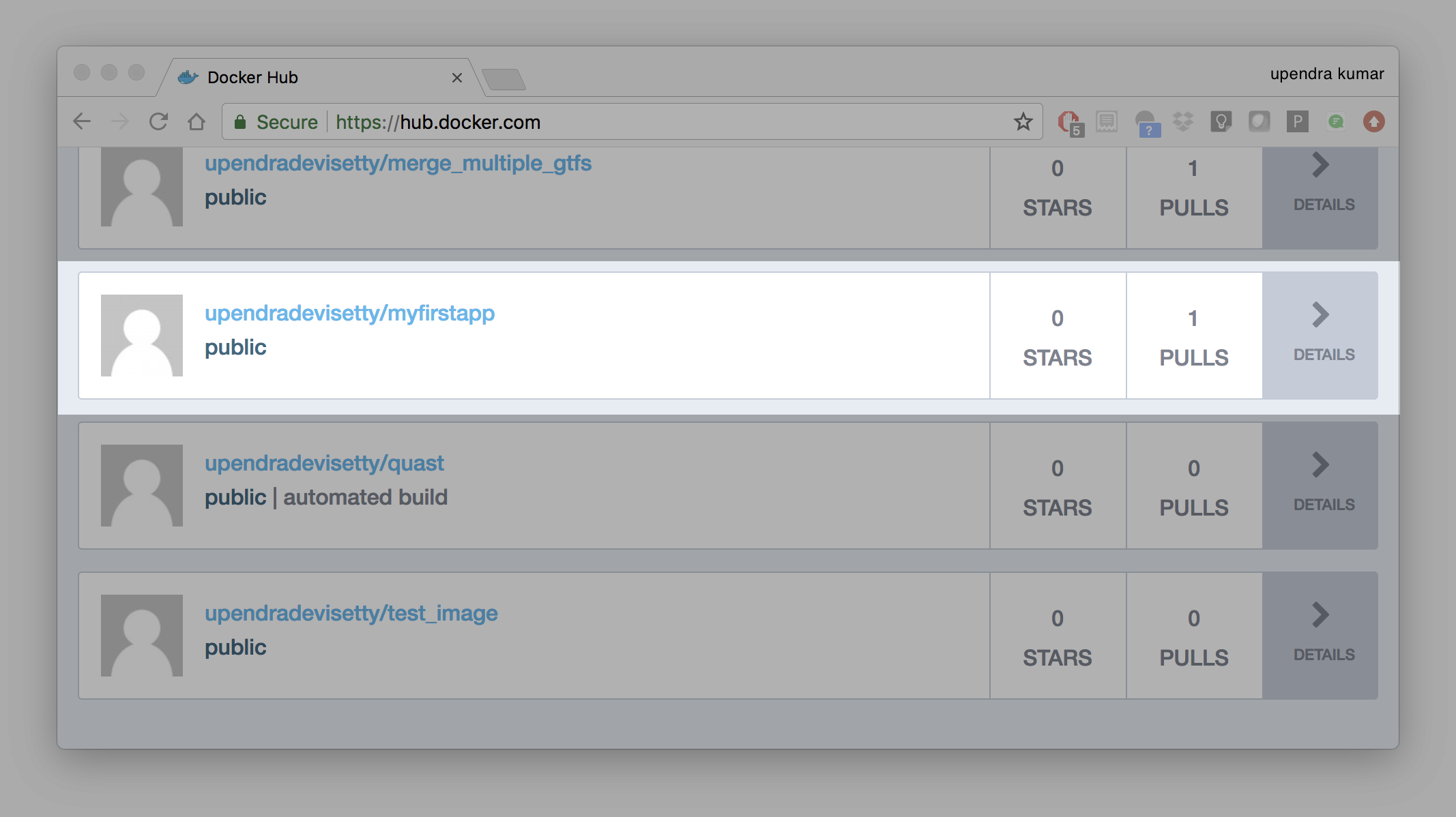

Once complete, the results of this upload are publicly available. If you log in to Docker Hub, you will see the new image there, with its pull command.

Congrats! You just made your first Docker image and shared it with the world!

1.1.4 Pull and run the image from the remote repository¶

Let’s try to run the image from the remote repository on Cloud server by logging into CyVerse Atmosphere, launching an instance

First install Docker on Atmosphere using from here https://docs.docker.com/install/linux/docker-ce/ubuntu or alternatively you can use ezd command which is a short-cut command for installing Docker on Atmosphere

$ ezd

Now run the following command to run the docker image from Dockerhub

$ sudo docker run -d -p 8888:8888 --name jupyter username/jupyter:1.0

Note

You don’t have to run docker pull since if the image isn’t available locally on the machine, Docker will pull it from the repository.

Head over to http://<vm-address>:8888 and your app should be live.

1.2 Private repositories¶

In an earlier part, we had looked at the Docker Hub, which is a public registry that is hosted by Docker. While the Dockerhub plays an important role in giving public visibility to your Docker images and for you to utilize quality Docker images put up by others, there is a clear need to setup your own private registry too for your team/organization. For example, CyVerse has it own private registry which will be used to push the Docker images.

1.2.1 Pull down the Registry Image¶

You might have guessed by now that the registry must be available as a Docker image from the Docker Hub and it should be as simple as pulling the image down and running that. You are correct!

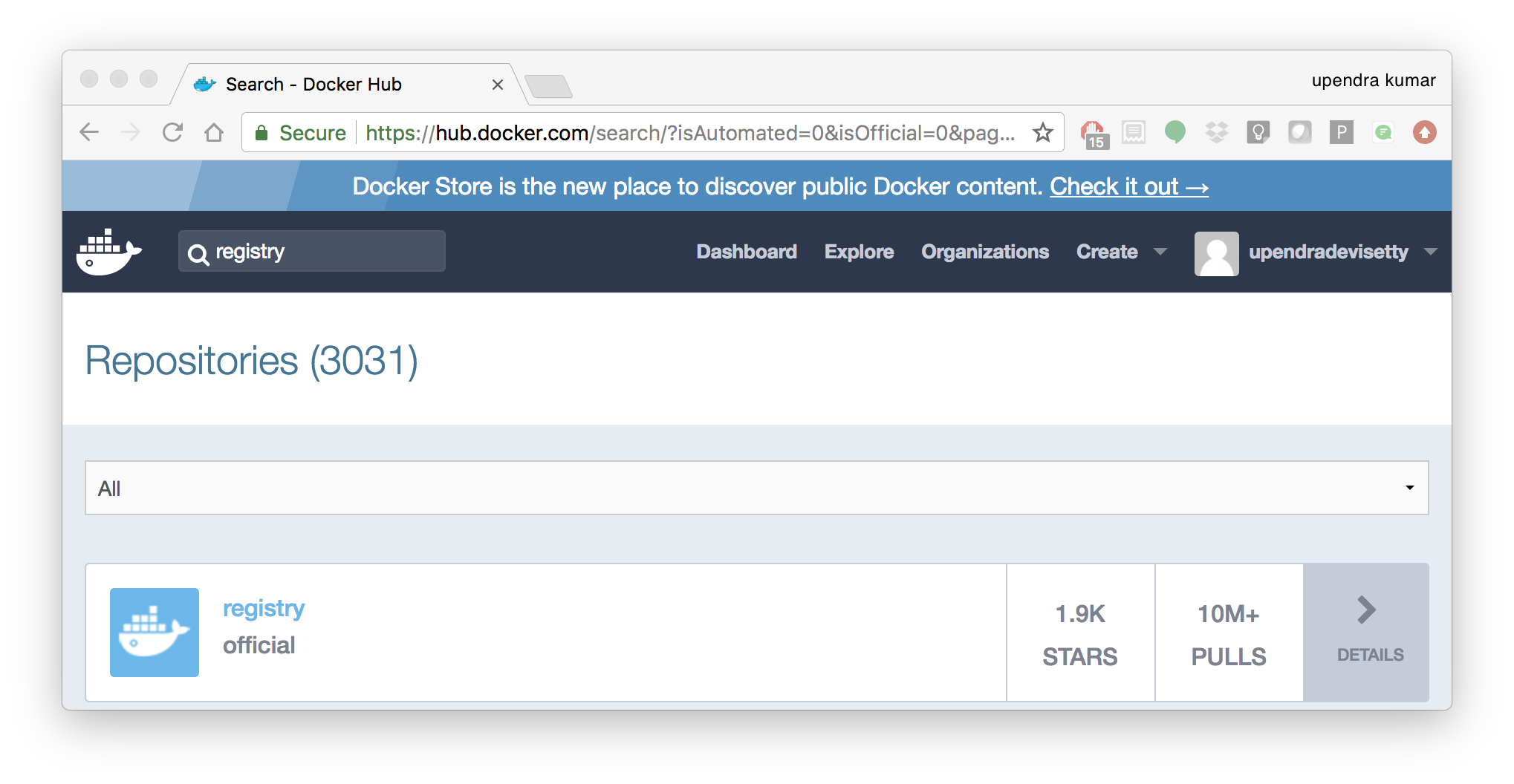

A Dockerhub search on the keyword registry brings up the following image as the top result:

Run a container from registry Dockerhub image

$ docker run -d -p 5000:5000 --name registry registry:2

Run docker ps -l to check the recent container from this Docker image

$ docker ps -l

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

6e44a0459373 registry:2 "/entrypoint.sh /e..." 11 seconds ago Up 10 seconds 0.0.0.0:5000->5000/tcp registry

1.2.2 Tag the image that you want to push¶

Next step is to tag your image under the registry namespace and push it there

$ REGISTRY=localhost:5000

$ docker tag $YOUR_DOCKERHUB_USERNAME/myfirstapp:1.0 $REGISTRY/$(whoami)/myfirstapp:1.0

1.2.2 Publish the image into the local registry¶

Finally push the image to the local registry

$ docker push $REGISTRY/$(whoami)/myfirstapp:1.0

The push refers to a repository [localhost:5000/upendra_35/myfirstapp]

64436820c85c: Pushed

831cff83ec9e: Pushed

c3497b2669a8: Pushed

1c5b16094682: Pushed

c52044a91867: Pushed

60ab55d3379d: Pushed

1.0: digest: sha256:5095dea8b2cf308c5866ef646a0e84d494a00ff0e9b2c8e8313a176424a230ce size: 1572

1.2.3 Pull and run the image from the local repository¶

You can also pull the image from the local repository similar to how you pull it from Dockerhub and run a container from it

$ docker run -d -P --name=myfirstapplocal $REGISTRY/$(whoami)/myfirstapp:1.0

2. Automated Docker image building from GitHub¶

An automated build is a Docker image build that is triggered by a code change in a GitHub or Bitbucket repository. By linking a remote code repository to a Dockerhub automated build repository, you can build a new Docker image every time a code change is pushed to your code repository.

A build context is a Dockerfile and any files at a specific location. For an automated build, the build context is a repository containing a Dockerfile.

Automated Builds have several advantages:

- Images built in this way are built exactly as specified.

- The Dockerfile is available to anyone with access to your Docker Hub repository.

- Your repository is kept up-to-date with code changes automatically.

- Automated Builds are supported for both public and private repositories on both GitHub and Bitbucket.

2.1 Prerequisites¶

To use automated builds, you first must have an account on Docker Hub and on the hosted repository provider (GitHub or Bitbucket). While Docker Hub supports linking both GitHub and Bitbucket repositories, here we will use a GitHub repository. If you don’t already have one, make sure you have a GitHub account. A basic account is free

Note

- If you have previously linked your Github or Bitbucket account, you must have chosen the Public and Private connection type. To view your current connection settings, log in to Docker Hub and choose Profile > Settings > Linked Accounts & Services.

- Building Windows containers is not supported.

2.2 Link your Docker Hub account to GitHub¶

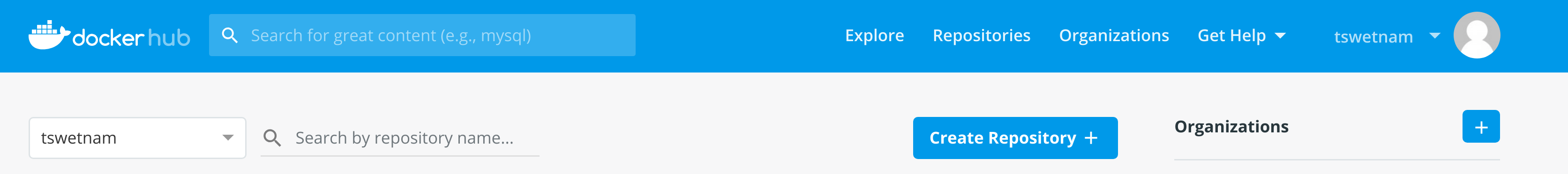

- Log into Docker Hub.

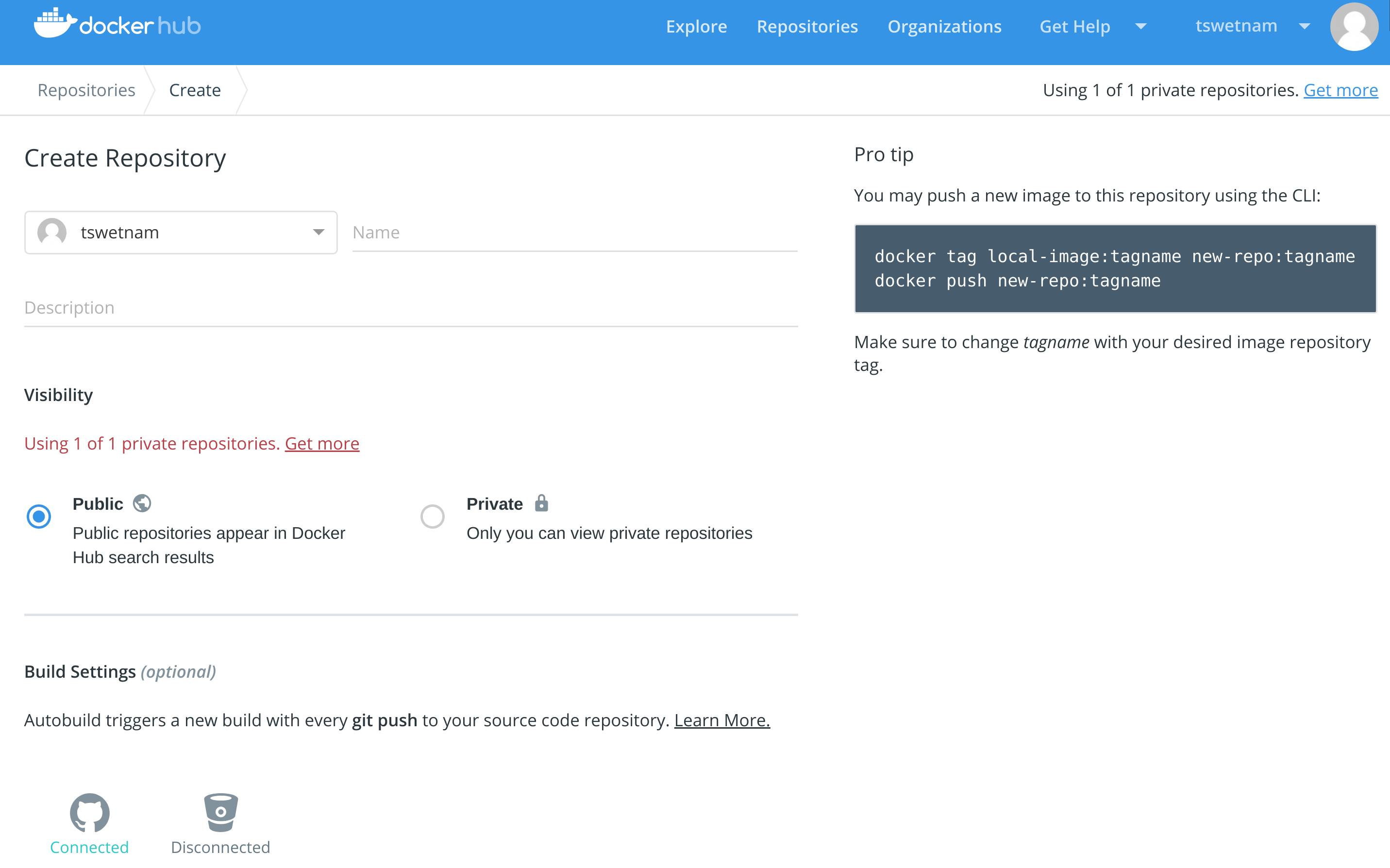

- Click “Create Repository+”

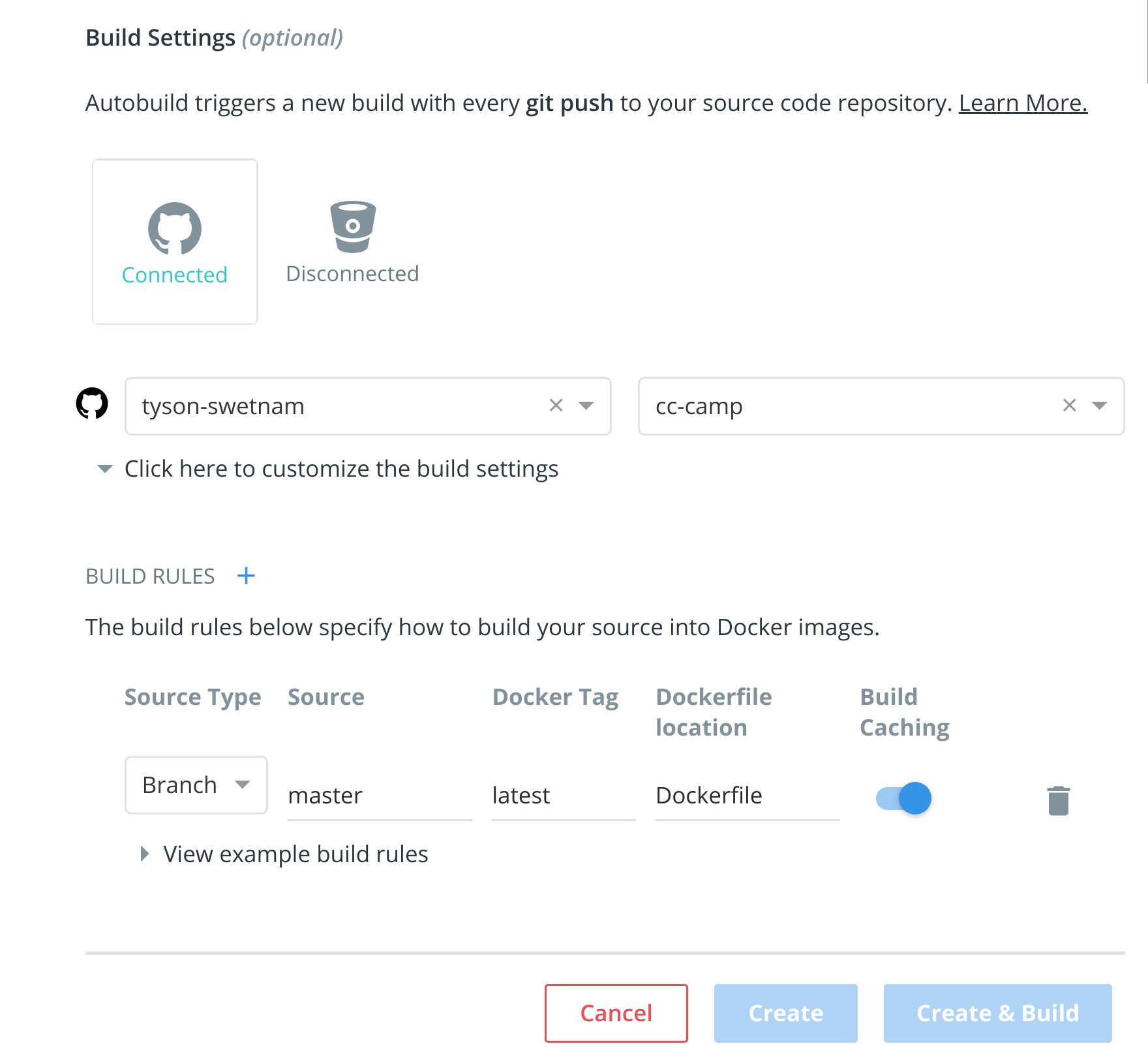

- Click the Build Settings and select

GitHub.

The system prompts you to choose between Public and Private and Limited Access. The Public and Private connection type is required if you want to use the Automated Builds.

- Press

Selectunder Public and Private connection type. If you are not logged into GitHub, the system prompts you to enter GitHub credentials before prompting you to grant access. After you grant access to your code repository, the system returns you to Docker Hub and the link is complete.

After you grant access to your code repository, the system returns you to Docker Hub and the link is complete. For example, github linked hosted repository looks like this:

2.3 Automated Container Builds¶

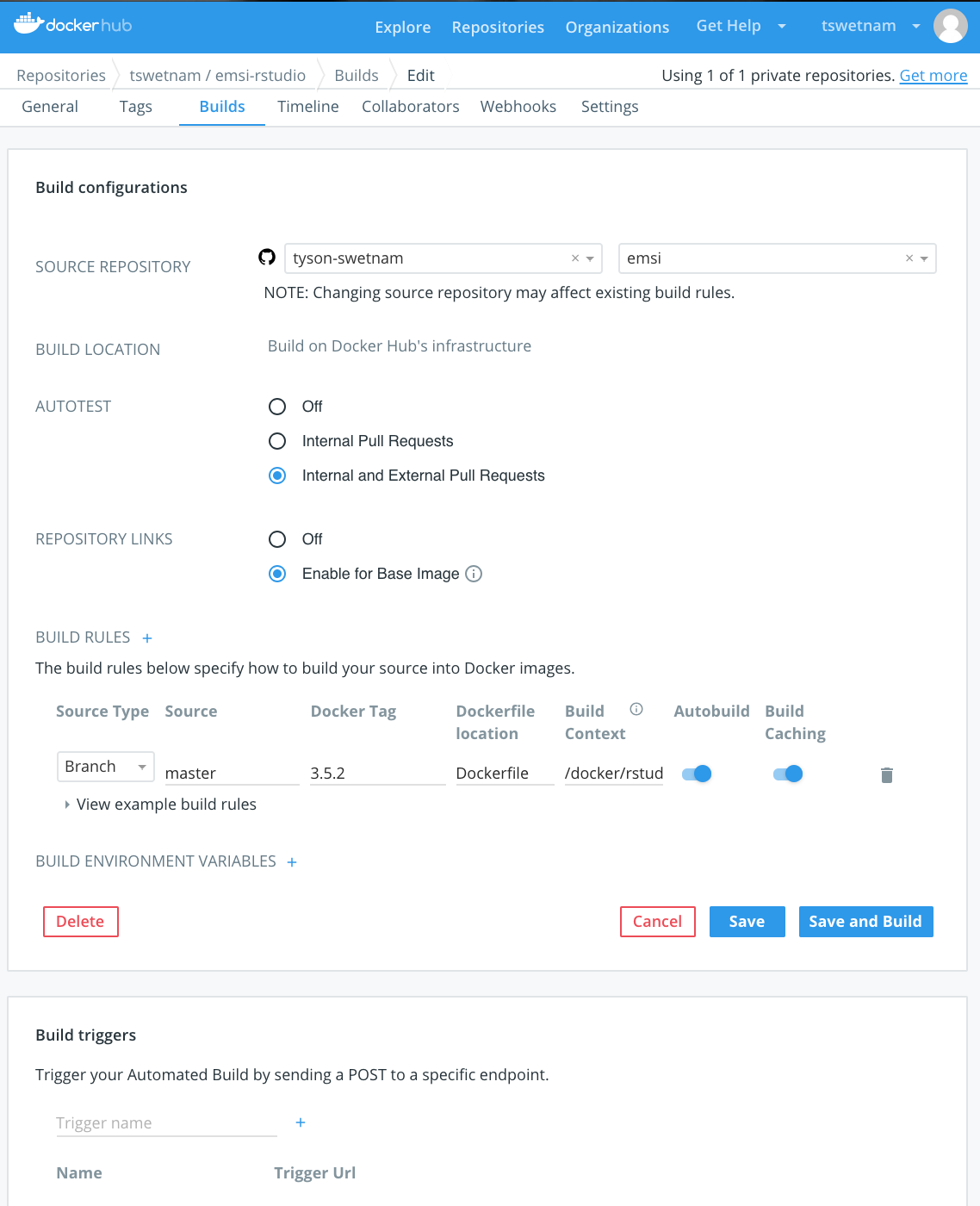

Automated build repositories rely on the integration with a version control system (GitHub or Gitlab) where your Dockerfile is kept.

Let’s create an automatic build for our container using the instructions below:

- Initialize git repository for the jupyter directory you created for your

Dockerfile

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/username/github/repository_name/

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

Dockerfileg

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

$ git add * && git commit -m"Add files and folders"

[master (root-commit) cfdf021] Add files and folders

4 files changed, 75 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 Dockerfile

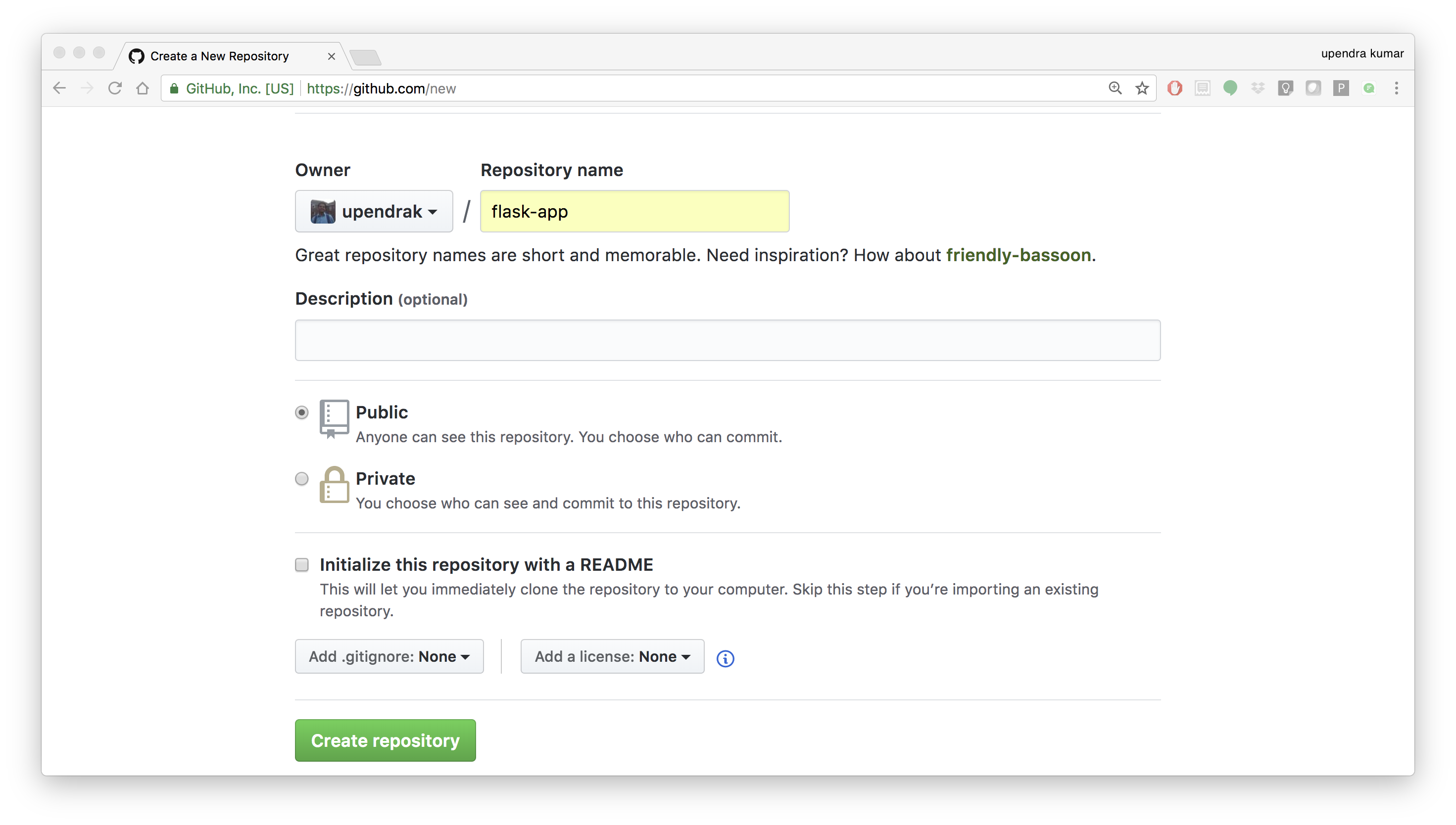

- Create a new repository on github by navigating to this url - https://github.com/new

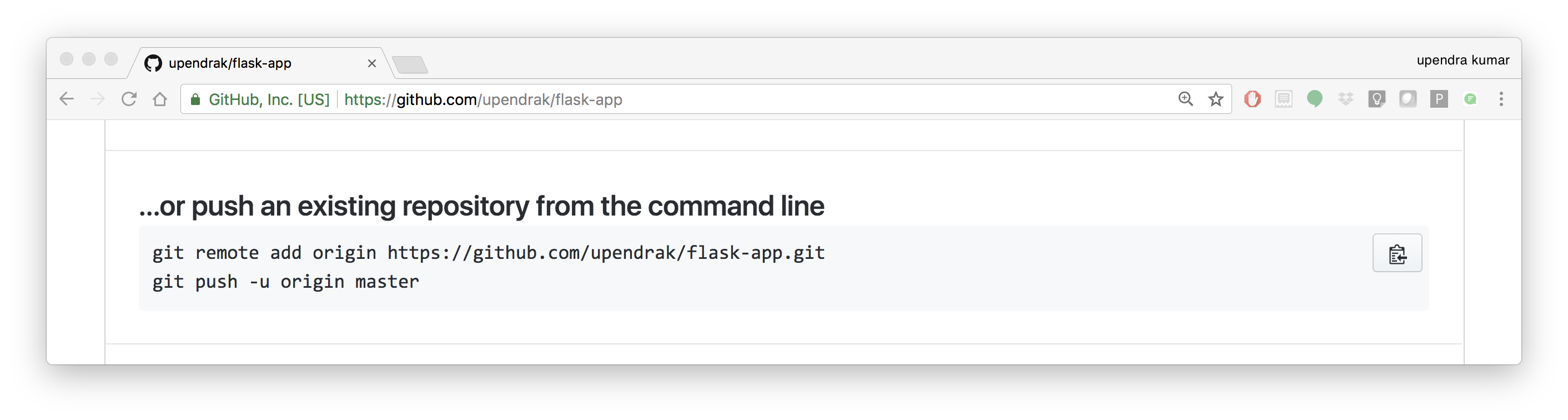

- Push the repository to github

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/username/jupyter.git

$ git push -u origin master

Counting objects: 7, done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Writing objects: 100% (7/7), 1.44 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 7 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/username/jupyter.git

* [new branch] master -> master

Branch master set up to track remote branch master from origin.

- Select

Create>Create Automated Buildfrom Docker Hub.

- The system prompts you with a list of User/Organizations and code repositories.

- For now select your GitHub account from the User/Organizations list on the left. The list of repositories change.

- Pick the project to build. In this case

jupyter. Type in “Container Camp Jupyter” in the Short Description box. - If you have a long list of repos, use the filter box above the list to restrict the list. After you select the project, the system displays the Create Automated Build dialog.

Note

The dialog assumes some defaults which you can customize. By default, Docker builds images for each branch in your repository. It assumes the Dockerfile lives at the root of your source. When it builds an image, Docker tags it with the branch name.

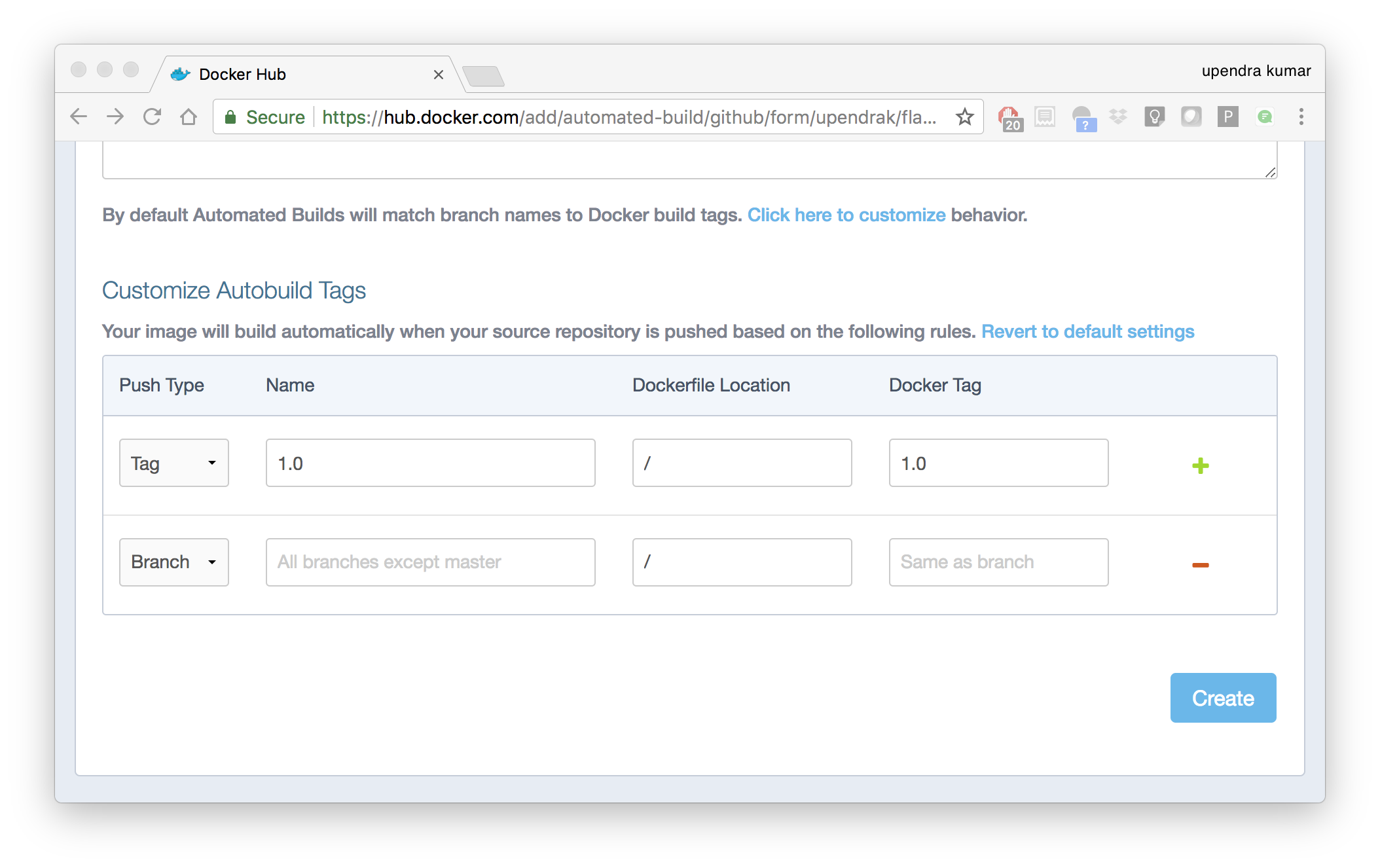

- Customize the automated build by pressing the

Click here to customizebehavior link.

Specify which code branches or tags to build from. You can build by a code branch or by an image tag. You can enter a specific value or use a regex to select multiple values. To see examples of regex, press the Show More link on the right of the page.

- Enter the

master(default) for the name of the branch. - Leave the Dockerfile location as is.

- Recall the file is in the root of your code repository.

- Specify

1.0for the Tag Name.

- Click

Create.

Important

During the build process, Docker copies the contents of your Dockerfile to Docker Hub. The Docker community (for public repositories) or approved team members/orgs (for private repositories) can then view the Dockerfile on your repository page.

The build process looks for a README.md in the same directory as your Dockerfile. If you have a README.md file in your repository, it is used in the repository as the full description. If you change the full description after a build, it’s overwritten the next time the Automated Build runs. To make changes, modify the README.md in your Git repository.

Warning

You can only trigger one build at a time and no more than one every five minutes. If you already have a build pending, or if you recently submitted a build request, Docker ignores new requests.

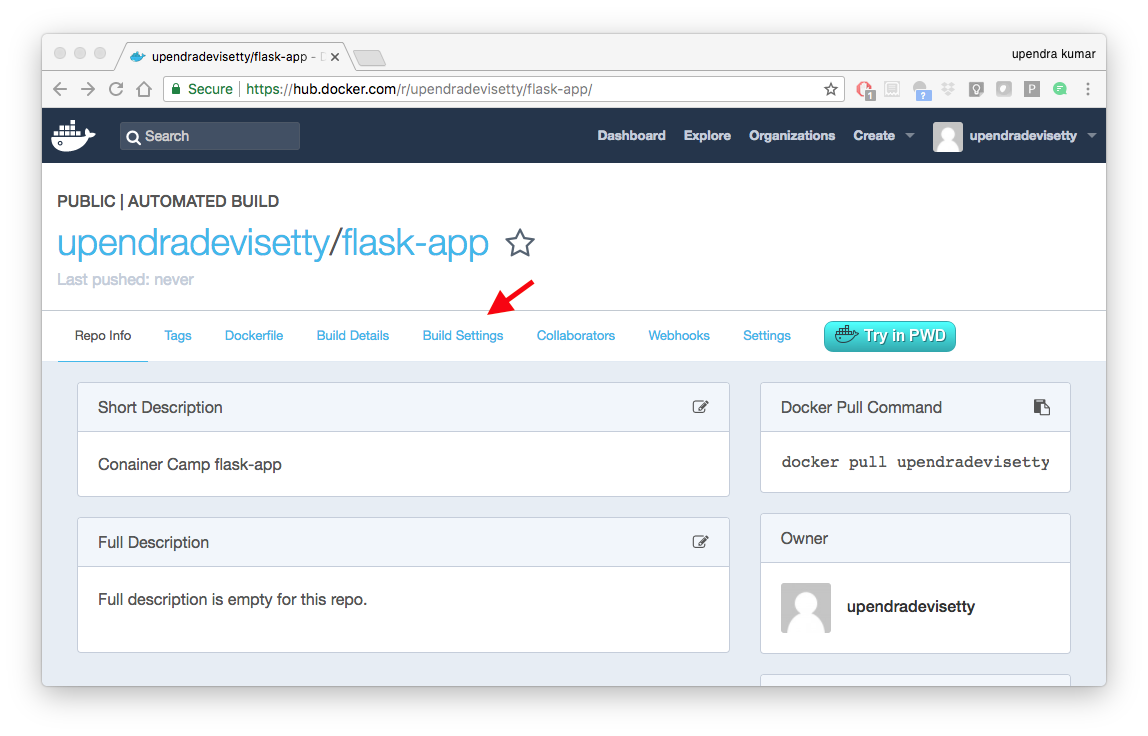

It can take a few minutes for your automated build job to be created. When the system is finished, it places you in the detail page for your Automated Build repository.

- Manually Trigger a Build

Before you trigger an automated build by pushing to your GitHub jupyter repo, you’ll trigger a manual build. Triggering a manual build ensures everything is working correctly.

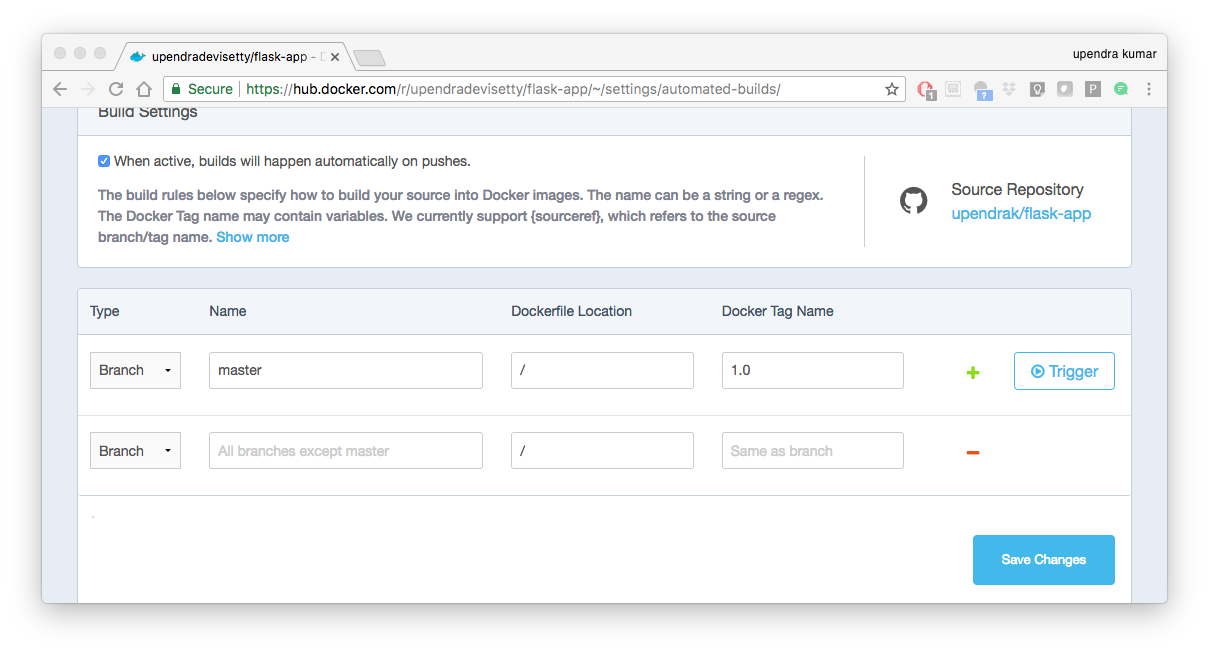

From your automated build page choose Build Settings

Press Trigger button and finally click Save Changes.

Note

Docker builds everything listed whenever a push is made to the code repository. If you specify a particular branch or tag, you can manually build that image by pressing the Trigger. If you use a regular expression syntax (regex) to define your build branch or tag, Docker does not give you the option to manually build.

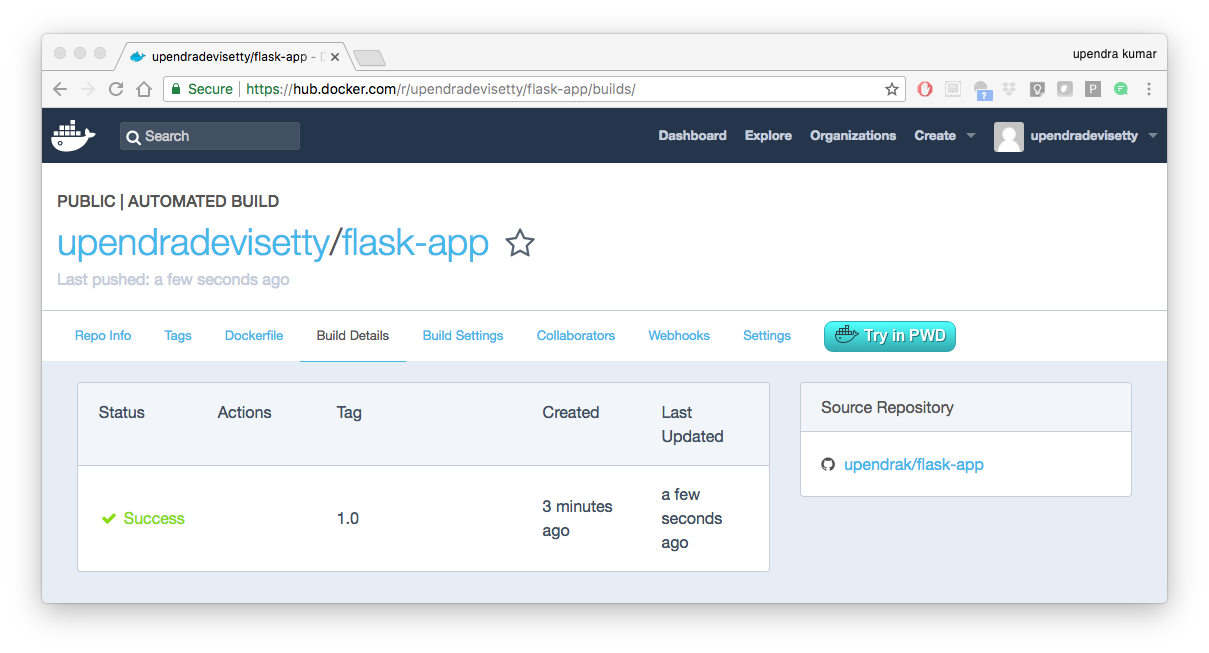

- Review the build results

The Build Details page shows a log of your build systems:

Navigate to the Build Details page.

Wait until your image build is done.

You may have to manually refresh the page and your build may take several minutes to complete.

Exercise 1 (5-10 mins): Updating and automated building¶

git add,commitandpushto your GitHub or Gitlab repo- Trigger automatic build with a new tag (2.0) on Docker Hub

- Pull your Docker image from Docker Hub to a new location.

- Run the instance to make sure it works

3. Managing Data in Docker¶

It is possible to store data within the writable layer of a container, but there are some limitations:

- The data doesn’t persist when that container is no longer running, and it can be difficult to get the data out of the container if another process needs it.

- A container’s writable layer is tightly coupled to the host machine where the container is running. You can’t easily move the data somewhere else.

- Its better to put your data into the container AFTER it is build - this keeps the container size smaller and easier to move across networks.

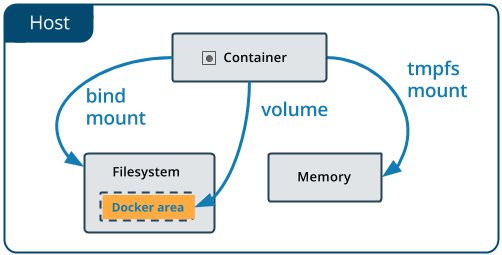

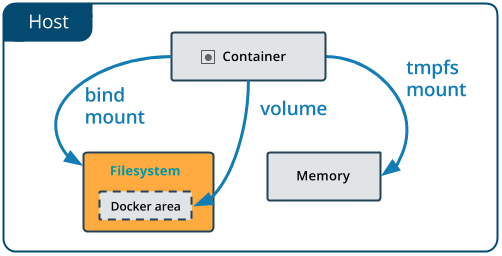

Docker offers three different ways to mount data into a container from the Docker host:

- volumes,

- bind mounts,

- tmpfs volumes.

When in doubt, volumes are almost always the right choice.

3.1 Volumes¶

Volumes are created and managed by Docker. You can create a new volume explicitly using the docker volume create command, or Docker can create a volume in the container when the container is built.

When you run a container, you can bring a directory from the host system into the container, and give it a new name and location using the -v or --volume flag.

$ docker run -v /home/username/your_data_folder:/data username/jupyter:latest

In the example above, you can mount a folder from your localhost, in your home user directory into the container as a new directory named /data.

When you create a Docker volume, it is stored within a directory on the Docker Linux host (/var/lib/docker/

Note

File location on Mac OS X is a bit different. `see here<https://timonweb.com/posts/getting-path-and-accessing-persistent-volumes-in-docker-for-mac/>`_.

A given volume can be mounted into multiple containers simultaneously. When no running container is using a volume, the volume is still available to Docker and is not removed automatically. You can remove unused volumes using docker volume prune command.

Volumes are often a better choice than persisting data in a container’s writable layer, because using a volume does not increase the size of containers using it, and the volume’s contents exist outside the lifecycle of a given container. While bind mounts (which we will see later) are dependent on the directory structure of the host machine, volumes are completely managed by Docker. Volumes have several advantages over bind mounts:

- Volumes are easier to back up or migrate than bind mounts.

- You can manage volumes using Docker CLI commands or the Docker API.

- Volumes work on both Linux and Windows containers.

- Volumes can be more safely shared among multiple containers.

- A new volume’s contents can be pre-populated by a container.

Note

If your container generates non-persistent state data, consider using a tmpfs mount to avoid storing the data anywhere permanently, and to increase the container’s performance by avoiding writing into the container’s writable layer.

3.1.1 Choose the -v or –mount flag for mounting volumes¶

Originally, the -v or --volume flag was used for standalone containers and the --mount flag was used for swarm services. However, starting with Docker 17.06, you can also use --mount with standalone containers. In general, --mount is more explicit and verbose. The biggest difference is that the -v syntax combines all the options together in one field, while the --mount syntax separates them. Here is a comparison of the syntax for each flag.

Tip

New users should use the --mount syntax. Experienced users may be more familiar with the -v or --volume syntax, but are encouraged to use --mount, because research has shown it to be easier to use.

-v or --volume: Consists of three fields, separated by colon characters (:). The fields must be in the correct order, and the meaning of each field is not immediately obvious.

- In the case of named volumes, the first field is the name of the volume, and is unique on a given host machine.

- The second field is the path where the file or directory are mounted in the container.

- The third field is optional, and is a comma-separated list of options, such as

ro.

3.2 Bind mounts¶

--mount: Consists of multiple key-value pairs, separated by commas and each consisting of a <key>=<value> tuple. The --mount syntax is more verbose than -v or --volume, but the order of the keys is not significant, and the value of the flag is easier to understand.

- The type of the mount, which can be bind, volume, or tmpfs.

- The source of the mount. For named volumes, this is the name of the volume. For anonymous volumes, this field is omitted. May be specified as source or src.

- The destination takes as its value the path where the file or directory is mounted in the container. May be specified as destination, dst, or target.

- The readonly option, if present, causes the bind mount to be mounted into the container as read-only.

Note

The --mount and -v examples have the same end result.

3.3 Create and manage volumes¶

Unlike a bind mount, you can create and manage volumes outside the scope of any container.

Let’s create a volume

$ docker volume create my-vol

List volumes:

$ docker volume ls

local my-vol

Inspect a volume by looking at the Mount section in the docker volume inspect

$ docker volume inspect my-vol

[

{

"Driver": "local",

"Labels": {},

"Mountpoint": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/my-vol/_data",

"Name": "my-vol",

"Options": {},

"Scope": "local"

}

]

Remove a volume

$ docker volume rm my-vol

3.3.1 Populate a volume using a container¶

This example starts an nginx container and populates the new volume nginx-vol with the contents of the container’s /var/log/nginx directory, which is where Nginx stores its log files.

$ docker run -d -p 8889:80 --name=jupytertest --mount source=jupyter-vol,target=/var/log/jupyter username/jupyter:latest

So, we now have a copy of Jupyter volume running inside a Docker container on our machine, and our host machine’s port 5000 maps directly to that copy of Jupyter’s port 80. Let’s use curl to do a quick test request:

cat jupyter-vol/_data/access.log

Use docker inspect jupyter-vol to verify that the volume was created and mounted correctly. Look for the Mounts section:

"Mounts": [

{

"Type": "volume",

"Name": "jupyter-vol",

"Source": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/jupyter-vol/_data",

"Destination": "/var/log/jupyter",

"Driver": "local",

"Mode": "z",

"RW": true,

"Propagation": ""

}

],

This shows that the mount is a volume, it shows the correct source and destination, and that the mount is read-write.

After running either of these examples, run the following commands to clean up the containers and volumes.

$ docker stop jupytertest

$ docker rm jupytertest

$ docker volume rm jupyter-vol

3.4 Bind mounts¶

Bind mounts: When you use a bind mount, a file or directory on the host machine is mounted into a container.

Tip

If you are developing new Docker applications, consider using named volumes instead. You can’t use Docker CLI commands to directly manage bind mounts.

Warning

One side effect of using bind mounts, for better or for worse, is that you can change the host filesystem via processes running in a container, including creating, modifying, or deleting important system files or directories. This is a powerful ability which can have security implications, including impacting non-Docker processes on the host system.

If you use --mount to bind-mount a file or directory that does not yet exist on the Docker host, Docker does not automatically create it for you, but generates an error.

3.2.1 Start a container with a bind mount¶

$ mkdir data

$ docker run -p 8888:8888 --name jupytertest --mount type=bind,source="$(pwd)"/data,target=/var/log/jupyter username/jupyter:latest

Use docker inspect jupytertest to verify that the bind mount was created correctly. Look for the “Mounts” section

This shows that the mount is a bind mount, it shows the correct source and target, it shows that the mount is read-write, and that the propagation is set to rprivate.

Stop the container:

$ docker rm -f juptertest

3.4.1 Use a read-only bind mount¶

For some development applications, the container needs to write into the bind mount, so changes are propagated back to the Docker host. At other times, the container only needs read access.

This example modifies the one above but mounts the directory as a read-only bind mount, by adding ro to the (empty by default) list of options, after the mount point within the container. Where multiple options are present, separate them by commas.

$ docker run -d -p 8888:8888 --name jupytertest --mount type=bind,source="$(pwd)"/data,target=/var/log/jupyter,readonly username/jupyter:latest

Use docker inspect jupytertest to verify that the bind mount was created correctly. Look for the Mounts section:

Stop the container:

$ docker rm -f jupytertest

Remove the volume:

$ docker volume rm jupytertest

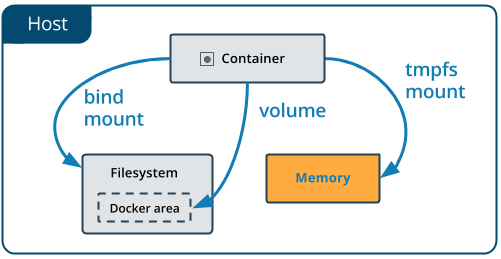

3.3 tmpfs Mounts¶

tmpfs mounts: A tmpfs mount is not persisted on disk, either on the Docker host or within a container. It can be used by a container during the lifetime of the container, to store non-persistent state or sensitive information. For instance, internally, swarm services use tmpfs mounts to mount secrets into a service’s containers.

Volumes and bind mounts are mounted into the container’s filesystem by default, and their contents are stored on the host machine. There may be cases where you do not want to store a container’s data on the host machine, but you also don’t want to write the data into the container’s writable layer, for performance or security reasons, or if the data relates to non-persistent application state. An example might be a temporary one-time password that the container’s application creates and uses as-needed. To give the container access to the data without writing it anywhere permanently, you can use a tmpfs mount, which is only stored in the host machine’s memory (or swap, if memory is low). When the container stops, the tmpfs mount is removed. If a container is committed, the tmpfs mount is not saved.

$ docker run -d -p 8888:8888 --name jupytertest --mount type=tmpfs,target=/var/log/jupyter username/jupyter:latest

Use docker inspect jupytertest to verify that the bind mount was created correctly. Look for the Mounts section:

$ docker inspect jupytertest

You can see from the above output that the Source filed is empty which indicates that the contents are not avaible on Docker host or host file system.

Stop the container:

$ docker rm -f jupytertest

Remove the volume:

$ docker volume rm jupytertest

4. Docker Compose for multi-container apps¶

Docker Compose is a tool for defining and running your multi-container Docker applications.

Main advantages of Docker compose include:

- Your applications can be defined in a YAML file where all the options that you used in

docker runare now defined (Reproducibility). - It allows you to manage your application as a single entity rather than dealing with individual containers (Simplicity).

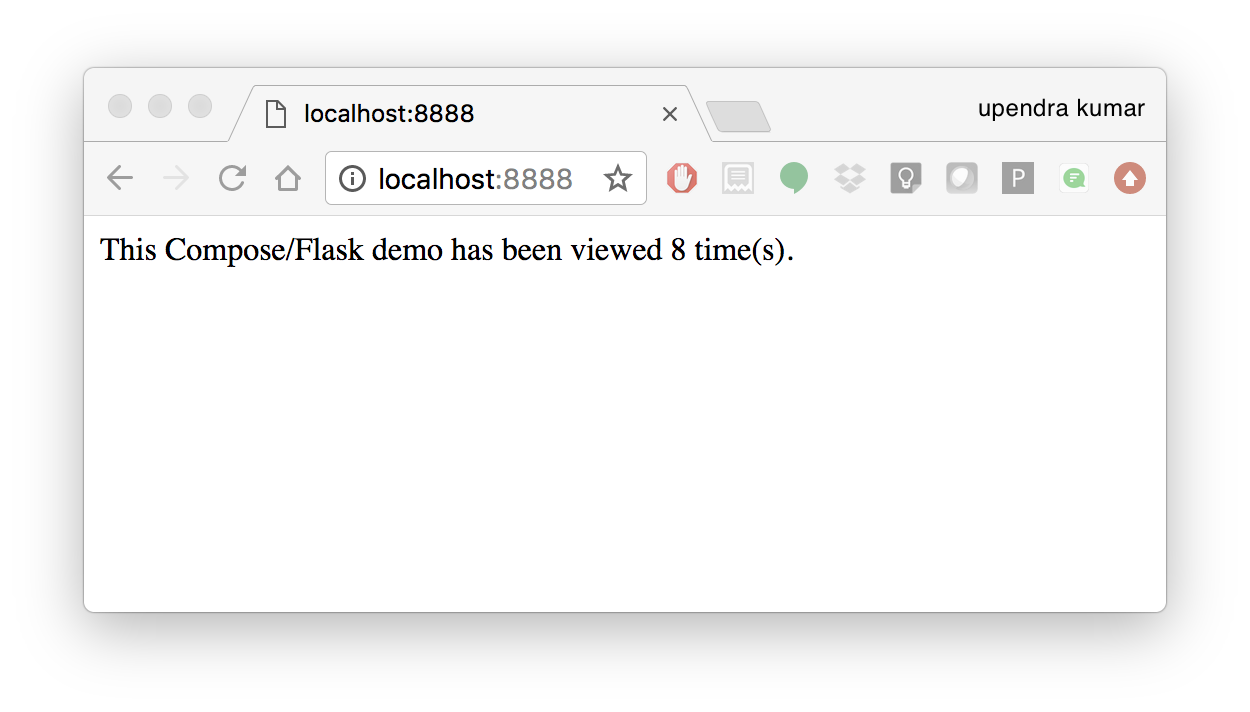

Let’s now create a simple web app with Docker Compose using Flask (which you already seen before) and Redis. We will end up with a Flask container and a Redis container all on one host.

Note

The code for the above compose example is available here

- You’ll need a directory for your project on your host machine:

$ mkdir compose_flask && cd compose_flask

- Add the following to requirements.txt inside compose_flask directory:

flask

redis

- Copy and paste the following code into a new file called app.py inside compose_flask directory:

from flask import Flask

from redis import Redis

app = Flask(__name__)

redis = Redis(host='redis', port=6379)

@app.route('/')

def hello():

redis.incr('hits')

return 'This Compose/Flask demo has been viewed %s time(s).' % redis.get('hits')

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run(host="0.0.0.0", debug=True)

- Create a Dockerfile with the following code inside

compose_flaskdirectory:

FROM python:2.7

ADD . /code

WORKDIR /code

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

CMD python app.py

- Add the following code to a new file,

docker-compose.yml, in your project directory:

version: '2'

services:

web:

restart: always

build: .

ports:

- "8888:5000"

volumes:

- .:/code

depends_on:

- redis

redis:

restart: always

image: redis

A brief explanation of docker-compose.yml is as below:

restart: alwaysmeans that it will restart whenever it fails.- We define two services, web and redis.

- The web service builds from the Dockerfile in the current directory.

- Forwards the container’s exposed port (5000) to port 8888 on the host.

- Mounts the project directory on the host to /code inside the container (allowing you to modify the code without having to rebuild the image).

depends_onlinks the web service to the Redis service.- The redis service uses the latest Redis image from Docker Hub.

Note

Docker for Mac and Docker Toolbox already include Compose along with other Docker apps, so Mac users do not need to install Compose separately. Docker for Windows and Docker Toolbox already include Compose along with other Docker apps, so most Windows users do not need to install Compose separately.

For Linux users

sudo curl -L https://github.com/docker/compose/releases/download/1.19.0/docker-compose-`uname -s`-`uname -m` -o /usr/local/bin/docker-compose

sudo chmod +x /usr/local/bin/docker-compose

- Build and Run with

docker-compose up -dcommand

$ docker-compose up -d

Building web

Step 1/5 : FROM python:2.7

2.7: Pulling from library/python

f49cf87b52c1: Already exists

7b491c575b06: Already exists

b313b08bab3b: Already exists

51d6678c3f0e: Already exists

09f35bd58db2: Already exists

f7e0c30e74c6: Pull complete

c308c099d654: Pull complete

339478b61728: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:8cb593cb9cd1834429f0b4953a25617a8457e2c79b3e111c0f70bffd21acc467

Status: Downloaded newer image for python:2.7

---> 9e92c8430ba0

Step 2/5 : ADD . /code

---> 746bcecfc3c9

Step 3/5 : WORKDIR /code

---> c4cf3d6cb147

Removing intermediate container 84d850371a36

Step 4/5 : RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

---> Running in d74c2e1cfbf7

Collecting flask (from -r requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading Flask-0.12.2-py2.py3-none-any.whl (83kB)

Collecting redis (from -r requirements.txt (line 2))

Downloading redis-2.10.6-py2.py3-none-any.whl (64kB)

Collecting itsdangerous>=0.21 (from flask->-r requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading itsdangerous-0.24.tar.gz (46kB)

Collecting Jinja2>=2.4 (from flask->-r requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading Jinja2-2.10-py2.py3-none-any.whl (126kB)

Collecting Werkzeug>=0.7 (from flask->-r requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading Werkzeug-0.14.1-py2.py3-none-any.whl (322kB)

Collecting click>=2.0 (from flask->-r requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading click-6.7-py2.py3-none-any.whl (71kB)

Collecting MarkupSafe>=0.23 (from Jinja2>=2.4->flask->-r requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading MarkupSafe-1.0.tar.gz

Building wheels for collected packages: itsdangerous, MarkupSafe

Running setup.py bdist_wheel for itsdangerous: started

Running setup.py bdist_wheel for itsdangerous: finished with status 'done'

Stored in directory: /root/.cache/pip/wheels/fc/a8/66/24d655233c757e178d45dea2de22a04c6d92766abfb741129a

Running setup.py bdist_wheel for MarkupSafe: started

Running setup.py bdist_wheel for MarkupSafe: finished with status 'done'

Stored in directory: /root/.cache/pip/wheels/88/a7/30/e39a54a87bcbe25308fa3ca64e8ddc75d9b3e5afa21ee32d57

Successfully built itsdangerous MarkupSafe

Installing collected packages: itsdangerous, MarkupSafe, Jinja2, Werkzeug, click, flask, redis

Successfully installed Jinja2-2.10 MarkupSafe-1.0 Werkzeug-0.14.1 click-6.7 flask-0.12.2 itsdangerous-0.24 redis-2.10.6

---> 5cc574ff32ed

Removing intermediate container d74c2e1cfbf7

Step 5/5 : CMD python app.py

---> Running in 3ddb7040e8be

---> e911b8e8979f

Removing intermediate container 3ddb7040e8be

Successfully built e911b8e8979f

Successfully tagged composeflask_web:latest

And that’s it! You should be able to see the Flask application running on http://localhost:8888 or <ipaddress>:8888

$ cat output.txt

Prediction of DecisionTreeClassifier:['apple' 'orange' 'apple']